More than 100 years ago, a Victorian building in Germantown was the bustling headquarters of one of the wealthiest Black entrepreneurs in the country.

John S. Trower, born before the end of slavery, moved to Philadelphia and established his business in the late 19th century, serving clients from around the region and securing contracts with major shipbuilders.

Perhaps just as important, he contributed part of his fortune to churches, schools and financial institutions in the African American community.

A small crowd gathered Sunday outside Trower’s former catering business — a blue, two-toned property now being operated as the Crab House on Germantown Avenue between Chelten Avenue and Vernon Park.

They dedicated a blue Pennsylvania historical marker, a project that has been years in the making.

Back in 2017, the Germantown United Community Development Corporation obtained a grant to help restore the building’s facade. That same year, the state historical commission approved an application for the marker.

It’s up to the applicant or building owner to pay for the signs, and, last year, a handful of neighborhood groups set up a committee to fundraise.

Markers cost upwards of $1,600, with additional expenses for installation, according to the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission.

The Trower building was also added last month to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, meaning it cannot be demolished or significantly altered without prior approval.

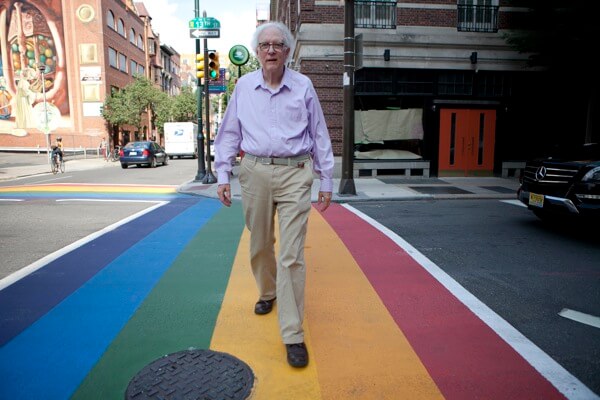

“My love for Germantown, its built environment, and its diverse heritage naturally led me to Trower,” said Oscar Beisert, of the Keeping Society of Philadelphia, who filed the papers for the historic register and marker.

“With one of the largest black populations in the country now and historically, Philadelphia possesses tremendous cultural resources related to African American heritage,” he added. “Yet far too many have been reduced to rubble, and are represented by what almost seem like blue tombstones.”

Trower was born to a free Black farming family in 1849 in Virginia. After reportedly paying off his mother’s house, he moved to Baltimore, where he found work shucking oysters, according to information provided by Historic Germantown.

He migrated to Philadelphia in the 1870s, first opening a catering business on Chelten Avenue. Several years later, he purchased the Germantown Avenue building, which was constructed in 1869 for use as a bank.

Trower’s big break came when William Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding Company hired his business to provide food service.

In Trower’s heyday, the facility was outfitted with a 150-seat dining hall, large bakery and an ice cream plant, according to a chapter dedicated to Trower in Booker T. Washington’s book “The Negro in Business.”

Catering and food service was one of the few industries that were open to Black businessmen in Trower’s time, and, even so, he did not serve customers of color, the Historic Germantown research found.

He also had an interest in real estate, owning multiple properties in Germantown and Ocean City, New Jersey.

Trower financed a few churches, including construction of the First African Baptist Church of Philadelphia in South Philadelphia, and helped purchase land for the Downingtown Industrial and Agricultural School in Chester County.

He also guaranteed mortgages for Black families and was a leader in a building and loan association for the community.

“I think the fact that he gave so much back and did so much good with his success was really a mark of what kind of person that he was,” said Paul Trower, the caterer’s great-grandson, one of a handful of his descendants who attended the historic marker designation.

Supreme Divine-Dow, executive director of the nearby Black Writers Museum, views Trower as an inspiration and said he operated on the principles of faith, education, entrepreneurship and business.

“He did it in the face of obstacles that we can’t even imagine,” Divine-Dow said. “In the face of lynchings that happened every day, in the face of terrorism that was enforced upon black folks. He continued to thrive.”