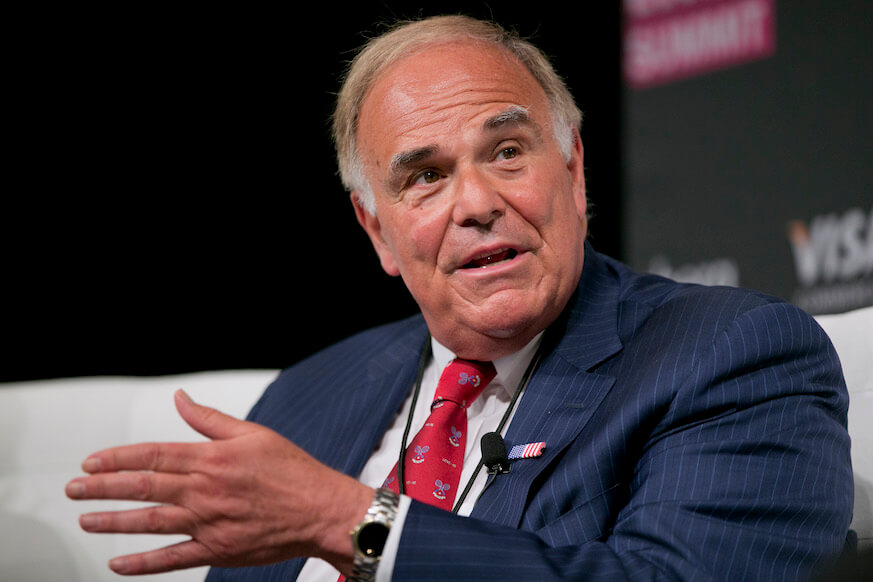

When word came last week that former Philly Mayor and Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell was linking up with the nonprofit Safehouse project – a public health response to rampant opioid use and a heroin supply laced with fentanyl, a location to protect addicts from danger, where they can use drugs under medical supervision and be given immediate attention if they overdose – tongues wagged. “It won’t be the only time I did something unpopular at its start,” said Rendell from his office. “It won’t be the last either.”

Those who know Rendell recall that this isn’t the first time he’s aided IV drug users, as 26 years ago, he was behind Philly’s first and (then) only needle exchange for drug users. “It was a good idea in 1992, because 50 percent of the people who contracted AIDS in Philadelphia – and in those days, AIDS was a death sentence – contracted the disease through the use of dirty needles, not sexual activity.”

At that time, the needle exchange Prevention Point program and its head Jose Benitez came to Rendell at told them of their wishes. “There was a two-fold benefit: it would insure people injected themselves with clean needles which would reduce the number of those dying and contracting AIDS,” said Rendell, pointing out how, 25-years-later, only 5 percent of needle drug users in this city contacted AIDS. “From that standpoint, Prevention Point has been an unqualified success. They not only give out free needles they discuss treatment alternatives to help break addiction.”

Last year, some 700-plus people went into programs due to the work of Prevention Point, to say nothing of the lives saved That’s why now, 26 years later — with the looming 2017 statistic of 1,271local overdose deaths, the highest in the nation – Rendell has teamed up with Benitez again for Safehouse.

“Most of those deaths in Philly happened in private homes to those who were alone, and because they were alone, they didn’t have access to Narcan and they die from an overdose. We now know most overdoses can be reversed almost immediately by the administration of Narcan,” said Rendell about the meds (Naloxone) used to block the effects of opioids. At the clean, safe injection sites that Rendell and Benitez are proposing, there will be doctors and nurses there, “to watch over a person shooting up, and if they OD, care for them, administer Narcan,” said Rendell. “And again, before they inject, there will be people there to discuss their addiction and suggestion treatment programs.”

The benefits realized by Benitez/Rendell’s teaming for Prevention Point have been solid and consistent, and would seem to make Safehouse a safe bet. ”It just makes common sense,” he said.

And yet, there is resistance. There are community fears, now as there were in the past, that come down to the possibility of those using drugs in a Safehouse facility hanging around that neighborhood and committing crimes. “There was no evidence of that happening in the entire 26 years at Prevention Point locations,” said Rendell. Mention to him that Kensington, Fishtown and Port Richmond have been rumored as a first Safehouse location (“that area was only mentioned because that was where most of the ODs occurred”), and Rendell states that they haven’t gotten that far as yet in singling out a location for a first Safehouse – if there is one location.

“We’re estimating that between 25 to 75 lives a year, to say nothing of millions of dollars in hospital costs, could be saved.” These estimates are based on like-minded models in Europe and Canada where safe houses have been in public use for decades. “That said, we don’t have a location in Philly. We’re seriously considering the option of a large, mobile unit to start. We’d have it in one location on Tuesday and another, say, on a Thursday, but it would have to be on a set schedule for it to work. We don’t have the money yet to set these sights up, and it’s not that easy to raise.”

Safehouse has, so far, a $200,000 grant for planning purposes. Rendell estimates that another $1.8 million is needed to kick off the program. “My guess is, though, if we raised half that, we could go forward.”

There are other public worries. No, Drugs will not be available at Safehouse. No. Doctors, nurses and other staffers will not help participants inject drugs. Getting needles for free and having that awaken users to the possibilities of drug use? Rendell just grunts. “That overlooks entirely what causes drug addiction, the very point that happens in the first place,” he said. “hey have an uncontrollable addiction — no one BECOMES an addict because needles are free.”

Rendell knows a little something about what makes addicts tick and making the opioid crisis personal. In 2016, John Decker, the son of his attorney pal Tad Decker, died of a heroin overdose at 30, alone in his parents’ house. “He was a great kid, and a friend with my son. John could have been anything he ever wanted, but he got injured playing sports, became addicted to opioids, and OD-ed and died alone. I can’t watch that happen over-and-over to kids in Philadelphia. It’s time for everyone to make it a personal issue. You won’t know who’s next — it is not confined to one ethnic or economic group,”

It can happen everywhere and to every family, and therefore must be stopped across the board. “What’s the harm in helping someone to not lose their life if we can save it?” quizzes Rendell. “Plus, we could talk to them and perhaps get them into rehabilitation and treatment.”

Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein told an WHYY listening audience that city officials could expect legal action if they permit Safehouse to open. U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams has discussed the Trump administration’s beliefs that safe injection sites violate federal law. On Friday, U.S. Attorney William M. McSwain told the Philly Inquirer and Daily News that Safehouse was “fundamentally illegal,” and that his office would make arrests to prevent Philadelphia from becoming the nation’s first safe injection site. “I’m not sure that people will follow me on this one,” said Rendell, who claimed that if this issue was polled today, it would probably poll negative. “I have always been willing, in my career, to do the unpopular, if I thought it was worth it,” said. Rendell. “This fight, a fight for people’s lives that can be saved, is worth it.”