Some 3,000 to 5,000 African-Americans were buried in a small cemetery belonging to the historic Bethel AME Church between 1810 and 1864. But after the church sold the land in 1899, it was turned into a park, Weccacoe Playground in Queen Village, at which children played for decades without knowing they were running just a few feet above the dead.

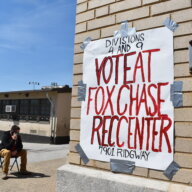

On Tuesday, the city formally closed the rec center that is physically atop a former cemetery for African-Americans, as they announced plans to create a new memorial to the burying ground’s history that will share space with the playground.

“The City of Philadelphia welcomes this opportunity to do right by the thousands interred at this site,” Philadelphia Managing Director Michael DiBerardinis said in a statement. “Whatever the memorial design turns out to be, it is important that it recognizes and honors the past, while remaining a gathering place for Philadelphians.”

The Bethel Burying Ground was brought back into the public eye in 2013 by local historian Terry Buckalew, who was concerned about city plans to renovate the playground disturbing historic materials.

An archaeological dig confirmed the presence of the cemetery under the playground. Dramatically, the first discovery confirming the burying ground’s presence was a tombstone, reading, “Amelia Brown, 1819, Aged 26 years. Whosoever live and believeth in me, though we be dead, yet shall we live.”

The burying ground was also in 2013 given a historic designation by the Philadelphia Historical Commission and added to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places.

“This site has deserved recognition for years and the Friends of Bethel Burying Ground and the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition are pleased that the city is finally taking steps toward giving proper respect to those interred,” said Michael Coard, a local attorney who is a member of Friends of the Bethel Burying Ground Coalition and the Bethel Burying Ground Memorial Committee.

According to the historical records, African-Americans were not allowed to buy cemeteries in the early 19th century, so the old Bethel AME Church and Rev. Richard Allen bought this plot on the 400 block of Queen Street. People buried at the Bethel Burying Ground “represent the founding generations of the nation’s largest and most important African American population of the 18th and 19th centuries,” said the mayor’s Office of Arts, Culture and Creative Economy (OACCE) in a statement.

The church stopped using the burying ground in 1864, and sold it off toward the end of the century. It was turned into a park by the city, and over the decades, all memory of the burying ground was lost, until Buckalew’s research. On his blog, BethelBuryingGroundProject.com, he has continued to share the histories of thousands of the dead buried there.

In the years since the discovery of the burying ground, playground renovations were halted, then took place in 2016 only over the area not including the burying ground. In the coming months, the city will work with community members and artists to design an appropriate memorial to the burying ground.

OACCE said several public events are planned to engage nearby communities in creating a physical memorial over the former burying ground.

“It is imperative that we develop a meaningful, physical memorialization of this historic site that reflects its role in our city’s history and honors those laid to rest there,” Mayor Jim Kenney said in a statement.

For more information, visit creativephl.org or bethelburyinggroundproject.com.