“I’m not a crusader.”

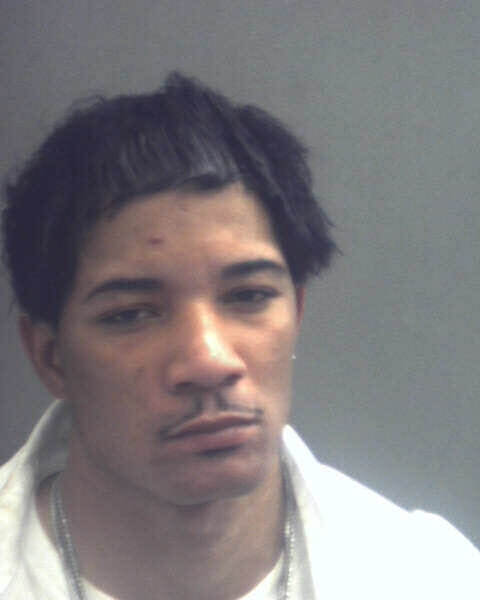

Philadelphia lawyer Nadeem Bezar is reflecting on the trial that concluded last week, where he represented a little girl who a foster care agency placed—twice—into the home of a sexual predator who violated her. Part of Bezar’s work consists of handling lawsuits related to child abuse. He is not someone who thinks the system needs to be totally overhauled, he said. But he is clearly infuriated by the cases where adults who are supposed to protect children do the opposite, whether through malicious intent or negligence. “You can’t take kids out of what you think is a bad environment and put them in a worse one, and you certainly can’t put them in a nightmare,” Bezar said. “This is the most vulnerable part of our population. These are kids that have already had their lives disrupted.” Last week, a jury decided that the social services organization theVillage, formerly known as Presbyterian Children’s Village, should pay $5.3 million for placing Bezar’s client, who was 7, into the home of now-convicted sexual predator Walter Ola Scott. Money from the verdict would go into a trust for the child. In a statement, theVillage said it is “evaluating its options” after the verdict.

“This has been a very emotional case for all parties involved, and we have tremendous sympathy for the plaintiff,” a spokesman said in a statement. “While we have the utmost respect for the judicial system and the decision of the jury in this case, we also respectfully disagree with several elements of the verdict and will be evaluating our options moving forward. As an organization, we are steadfastly committed to keeping our focus on the safety and well-being of those entrusted to our care.” Scott is now in prison, convicted of endangering the welfare of a child and indecent assault of a child for the abuse of three children who came into his home as foster kids — two from theVillage, one from another agency. One of the victims was Bezar’s client. “The levels of abuse vary with each one from unspeakable to horrible,” Bezar said of the three victims.

Bezar’s client was placed in Scott’s home for just three days the first time.

Afterward, she reported that she had been sexually abused to her long-term foster parent, who shared the information with a psychiatrist, he said. Yet four months later, she was placed there again, this time for five days. “The Scott home should never have been selected as a resource [foster] home,” Bezar said. “The child had disclosed enough information that an investigation as to what else is going on should have been done and that would have prevented other kids from going into that home.” But she was put back into the custody of a monster, he said. And more unspeakable things happened.

According to Bezar, another foster care agency had marked the Scott home “do not use.” The home was even being investigated by Child Protective Services when his client was placed there the second time. And interviewing Scott’s own children might have led representatives of theVillage to conclude they could not place children there, he said. “Why would you not ask his kids what it’s like?” Bezar asked. “If they had scratched beyond the surface, they would have found it.”

Bezar and fellow attorney Emily Marks tried the case. Hesaid that at trial, defense attorneys for theVillage expressed remorse for what happened to Bezar’s client. They claimed privacy and HIPAA laws prevented them from sharing that his client had reported sexual abuse, while defending their screenings and background checks, which Scott was able to pass. “Bad people have gotten better at being bad,” Bezar said. “We have to be very mindful of who we allow around our kids, because the people that want to be around them for the wrong reasons have gotten very good at disguising that so that they can get access.” Bezar doesn’t believe the foster care agency ever wanted anything bad to happen his client, but hopes the jury’s verdict will serve as a wake-up call for other foster care agencies about how to best protect children. As for his client, he can only hope for the best.

“The imprint that these kinds of events leave can be lifelong,” Bezar said. “We hope that everything works out for the best, and that she does as well as can be expected, but we don’t know with kids who have been harmed like this.” His client, now 11, has since been adopted by relatives of her birth parents.