When Jeff Thomas talks seriously about selling the now-legendary log cabin that he built with his own hands in Northern Liberties in 1985, there is, of course, a sense of sorrow and of loss.

How could there not be: Thomas, now 70, has lived for 32 years in this cozy, custom-built space at 878 N. Lawrence Street space crafted from oak planks and West Virginia poplar logs decades before this once-dilapidated block’s renaissance of tiny housing.

“I’m part of the change,” said Thomas, sitting before a roaring fireplace with his 10-year-old terrier Sparky at his feet. “I had other houses and lots on this block that I’ve sold — one right in front of me. I can’t complain about so-called bastards ruining this neighborhood with their modern condos and their gentrification. I’m one of those bastards.”

Like other bohemian artists and early adopters who moved to and built up Northern Liberties, Thomas is responsible for creating that neighborhood’s inventively expressive cosmopolitan flair and, therefore, its potential for upscale ascension.

It cost him $50,000 and a year and a half of his life to build on what was four vacant lots. Now he’s asking $639,000 for a two-room, two-floor space with parking. One thing that gets lost in translation, however, is the fact that the cabin is but one more chapter, one more art piece, in Thomas’ life and work as an artist.

“My body of work is like one long book. The cabin is just one more aspect of that, one that I just happen to live inside,” he said.

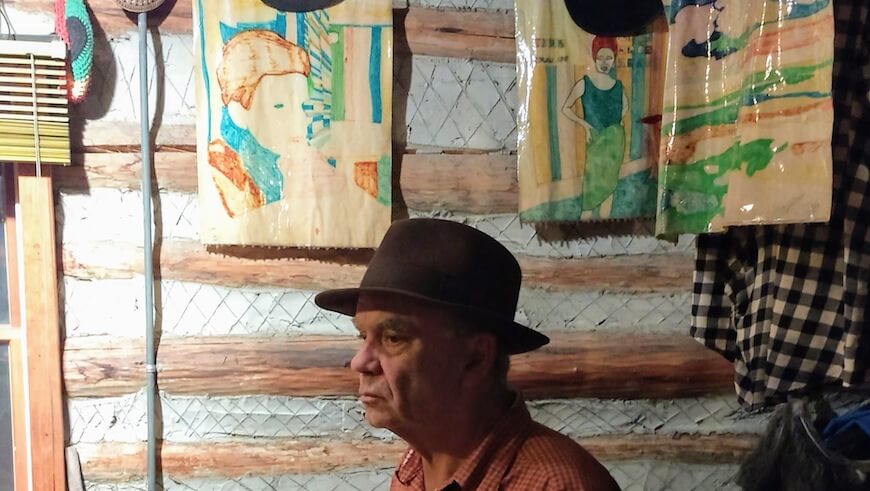

Currently displaying smaller works such as his colorful, acrylic-coated, hanger-mounted, “closet art” at Dirty Frank’s Off the Wall Gallery, the Philadelphia College of Art graduate is renowned for his immense sense of scale and the tactile: rough sculptural work often made from metallic elements, stone, trees, weathered driftwood, flotsam and jetsam from rivers and beaches, and household tools and implements. The cabin itself was based upon a childhood preoccupation of playing with Lincoln Logs.

“I have an eye for and a feel for nature,” he said quietly of his aesthetic history and how it translates into his sculptures and paintings, past and present. “With this cabin, I just knew instinctively how to construct it. And it’s all up to code.” Thomas tells a funny story about finishing the cabin with engineers, building inspectors and one 300-pound-man in tow, the latter whose sole reason for being there was to jump up-and-down in place from the cabin’s second floor.

“He was there to prove how sound this structure was. It was, and it is. This place is built like a ship,” he said.

The ladder-like steps going from floor one to two proves as much as it has the feel of a yacht’s staircase.

Poring through records and catalogs of past exhibitions from within this decade, Thomas has shown and curated events at the Highway Gallery such as “The Shovel Show,” an industrial, woodshedding exhibition that would look right at home in his rustic log cabin. His next move might be to show large-scale work at the upcoming Cherry Street Pier warehouse in 2018.

“The point is this cabin, no matter what the scale, is part of my history of work. This is my art,” he said.

As an artist, Thomas is restless, and 32 years is a long time in one place, no matter how custom-built his cabin may be. So he’s looking to move within the area —“a loft where Sparky and I can be conformable” — and the nearly $700,000 price tag for selling his log cabin will be cushion enough for him to live out his days.

As an artist, he knows that once he’s sold his cabin, his live-inn sculpture could be demolished to make way for another set of condos or new, brick housing on the block — a problem currently facing Old City’s for-sale Painted Bride Arts Center and its historic Isaiah Zagar mural.

With that, Thomas’ legendary log cabin — a landmark of Northern Liberties past and present — is both permanent and temporal; and of course, it’s difficult to say goodbye. “That’s the nature of art,” he said. “Once you finish it, it’s in the hands of the new owner, who can do what they like. That’s the cycle.”